![Guest Contributor Badge]() In this article-length guest blog post, retired U.S. Forest Service research forester Stephen F. Arno discusses why fire management is impeded today and says we need to look at the history of fire policy in tandem with the development of the science of disturbance ecology to gain a better understanding of the issue.

In this article-length guest blog post, retired U.S. Forest Service research forester Stephen F. Arno discusses why fire management is impeded today and says we need to look at the history of fire policy in tandem with the development of the science of disturbance ecology to gain a better understanding of the issue.

Numerous books and commentaries have described the century-long evolution of forest fire policy in the United States. However, rarely have these accounts focused on one of the seminal factors that provoked a transformation in policy and fire-control practices—namely, expanding knowledge of fire ecology.

Soon after its inception in the early 1900s the U.S. Forest Service adopted a policy that can be described as “fire exclusion,” based on the view that forest fires were unnecessary and a menace.[1] In the late 1970s, however, the agency was compelled by facts on the ground to begin transitioning to managing fire as an inherent component of the forest.[2] This new direction, “fire management,” is based on realization that fire is inevitable and can be either destructive or beneficial depending largely on how fires and forest fuels are managed. Despite the obvious logic of fire management it continues to be very difficult to implement on a significant scale. To understand why fire management is impeded and perhaps gain insight for advancing its application, we need to look at the history of fire policy in tandem with the development of the science of disturbance ecology. It is also important to review changing forest conditions and values at risk to wildfire. Certain aspects of the situation today make it more difficult to live with fire in the forest than was the case a century ago.

![Forest homes burned in the 2002 Rodeo-Chediski wildfire, AZ. Such a scene is increasing in frequency. (Photo by Humphrey’s Type 1 USDA/USDI Southwest Region Incident Management Team)]()

Forest homes burned in the 2002 Rodeo-Chediski wildfire, AZ. This is an increasingly common scene. (Photo by Humphrey’s Type 1 USDA/USDI Southwest Region Incident Management Team)

This story begins with the emergence of the profession of forestry in America at the turn of the twentieth century. The first professional foresters in the United States were educated in humid regions of Europe, where concepts of forestry developed primarily to establish tree plantations on land that had been denuded by agrarian people seeking firewood and building material and clearing forestland for grazing.[3] Native forests in these regions had largely disappeared long before, and fire in the forest was considered an undesirable, damaging agent. In retrospect, the European model of forestry didn’t apply very well to the vast areas of North American forest consisting of native species that had been maintained for millenniums by periodic fires. For instance, much of the Southeast and a great deal of the inland West supported forests of fire-resistant pines with open, grassy understories, perpetuated by frequent low-intensity fires.

From the outset, American foresters had to confront damaging wildfires, often caused by abandoned campfires, sparks from railroads, and people clearing land. Arguments for “light burning” to tend the forest were first made in print during the 1880s, before there were forest reserves or an agency to care for them.[4] Timber owners in northern California liked setting low-intensity fires under ideal conditions as a means of controlling accumulation of fuel. Stockmen liked to burn in order to stimulate growth of forage plants. Settlers used fire for land clearing and farming. Romanticists favored it for maintaining an age-old Indian way of caring for the land.

Fire historian Stephen Pyne concludes that there was no presumptive reason why American forestry should have rigorously fought against all forms of burning in the forest.[5] What the new government foresters like Gifford Pinchot and William Greeley refused to accept was that frontier laissez-faire burning practices could be allowed to coexist with systematic fire protection, which increasingly became the forester’s mission. But foresters saw light burning as a political threat, and they refused entreaties from advocates of burning to develop procedures for applying fire as a forestry practice.[6] Ironically, promoters of light burning were in a sense recognizing that it is important to account for natural processes in managing native forests, a concept termed “ecosystem management” when it was finally endorsed by the chief of the Forest Service in 1992.[7]

The “light burning” controversy ramped up considerably in 1910. President William Howard Taft, who succeeded Theodore Roosevelt in 1909, appointed Richard Ballinger as Secretary of the Interior. Soon Ballinger was accused of virtually giving away federal coal reserves to his industrialist friends by Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot, who publicly denounced Ballinger for corruption. Unable to control Pinchot, President Taft fired him in January of 1910, an action that sparked a national controversy since Pinchot was highly respected as a leader of the conservation movement. The fact that Pinchot’s nemesis, Ballinger, supported light burning—stating “we may find it necessary to revert to the old Indian method of burning over the forests annually at a seasonable period”—certainly didn’t help that cause gain favor with foresters. By unhappy coincidence, in August 1910, the same month that “the Big Burn” consumed 3 million forested acres in the Northern Rockies, Sunset magazine published an article by timberland owner George Hoxie calling for a government program to conduct light burning throughout California forests.[8] (The fact that the Big Burn occurred primarily in wetter forest types more susceptible to stand-replacing fire than most California forests was not generally recognized nor understood, in large part because there was little understanding of forest ecology at the time.) After the Big Burn, Forest Service leaders claimed they could’ve stopped the disaster if they’d had enough men and money. That mindset took hold of the agency and echoes down through to today in some corridors.

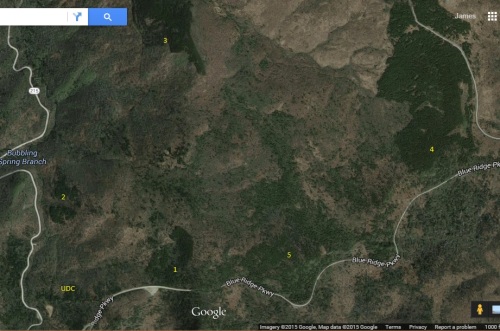

![Pulaski tunnel]()

Pulaski tunnel, September 1910. The Big Burn made a folk hero of ranger Ed Pulaski when he forced his men to take refuge from the fire in an old mine shaft. The fire also convinced agency leaders that more men and money could’ve prevented the disaster.

In October 1910, Pinchot’s successor Henry Graves visited T. B. Walker’s extensive timberlands in northeastern California.[9] Graves viewed tracts of ponderosa pine-mixed conifer forest that Walker’s crew had methodically “underburned” (a low-intensity surface fire under the trees) after the first fall rains in order to reduce hazardous fuel and brush. Graves didn’t deny the effectiveness of the treatment, but felt it was bad to kill seedlings and saplings. More than that, he didn’t like the idea of condoning use of fire in the forest. It didn’t help that one of Walker’s light burns had escaped earlier in the year and raced across 33,000 acres before submitting to control. Then, like now, deliberate burning in the forest was not risk free; however, light burning was aimed at reducing the greater hazard of severe wildfires.

Ironically, in 1899 Pinchot had published an article in National Geographic magazine containing many observations on the importance of historic fires in propagating economically important and iconic trees including longleaf pine, giant sequoia, coastal Douglas-fir, and western larch. Pinchot noted that had fires been kept out of the great Douglas-fir forests of western Washington, “the fir which gives them their distinctive character would not be in existence, but would be replaced by the [smaller and less valuable] hemlock . . . with its innumerable seedlings.”[10] Nevertheless, Pinchot clearly advocated control of forest fires.

![Scars from individual fires can be seen on the cross-section of a century-old “pitch stump” of ponderosa pine. (US Forest Service photo)]()

Scars from individual fires can be seen on the cross-section of a century-old “pitch stump” of ponderosa pine. (US Forest Service photo)

There were other inklings that fire might be useful in forestry. In a 1910 Forest Service publication, pioneering ecologist Frederic Clements advocated using controlled fire in the management of high-elevation lodgepole pine forests.[11] On the other hand, Clements and his contemporaries developed widely adopted models of forest succession that fostered a belief that undisturbed “climax” forests, the end-point of succession, were more desirable than forests maintained in a “sub-climax” state by periodic fires even if those disturbances had occurred naturally.[12] The successional models appealed to foresters because they implied that keeping fire out and allowing dense forests to develop would lead to greater production of timber. The models appealed to early ecologists as well perhaps because they suggested that the most desirable forest was one protected from “disturbance,” whether by fire, windstorms, or human activities.

The debate in California between advocates of light burning and foresters that championed fire exclusion, continued until about 1930. By then, the U.S. Forest Service had amassed abundant in-house studies and overwhelming political influence supporting its well-funded program of comprehensive fire protection. Early Forest Service studies of fire scars on trees confirmed that a history of frequent low-intensity fires characterized California’s magnificent mixed-conifer forests that featured giant ponderosa and sugar pines. But the agency asserted that fire scars hastened death and at least lowered the value of trees for lumber. Also, they felt that because fires killed seedlings and saplings, they prevented the forest from becoming fully stocked and producing the maximum quantity of timber. These seemed to be plausible judgments, based on a concept that the West’s native forests could eventually be farmed much like forest plantations in Europe.

FIRE IN THE SOUTH

The South, particularly its valuable longleaf pine forests, became the stage for pressuring the U.S. Forest Service and the forestry profession to accept burning as a necessary practice and thereafter to employ its resources to develop methods and technology for controlled burning. Paradoxically, Yale University’s School of Forestry, established through the efforts of Forest Service founders Pinchot and Henry Graves, produced the definitive evidence that controlled burning was essential to management of the South’s symbolic pine.

In early colonial times a forest dominated by longleaf pines covered an estimated 60 million acres along the broad Coastal Plain from east Texas to Virginia. Like the West’s ponderosa pine forests, the original longleaf woodlands were mostly open-grown and grassy beneath, and were perpetuated by frequent fires. One native traveler in 1841 described this forest as nearly pure longleaf pine “rolling like waves in the middle of the great ocean . . . The grass grows three feet high. And hill and valley are studded all over with flowers of every hue.”[13]

However by the 1910s when federal forestry began focusing on the South, its forests were being indiscriminately logged and grazed by cattle and hogs, and longleaf pine was not regenerating. Biologists speculated that fire might be important in restoring the pinelands, and a professor at Yale’s School of Forestry, H. H. Chapman, began long-term studies of the effects of fire exclusion and controlled burning. Excluding fire allowed low brush, palmetto, and other combustible vegetation, known as the “Southern rough,” to build up rapidly. Chapman found that the rough could out-compete pine seedlings, but also that the practice of annual burning to control the rough killed pine seedlings. However, burning at intervals of a few years controlled the rough and allowed longleaf pine seedlings to attain a larger, fire-resistant size. This periodic burning also controlled brown-spot needle disease that often killed seedlings.[14]

Chapman’s publicized findings supported periodic burning and were bolstered by other studies that showed burning the pinelands enhanced their forage value for livestock. Also, the U.S. Biological Survey published studies in 1931 showing that fire was essential for maintaining habitat for the South’s premiere game bird, the bobwhite quail. Moreover, the rapid buildup of Southern rough as a hazard for uncontrollable wildfires compelled many field foresters to stubbornly urge Forest Service administrators to allow controlled burning. By 1934, the Forest Service’s own Southern Research Station was covertly recommending to administrators that controlled burning be allowed if done for specified objectives by skilled technicians.[15]

Forest Service headquarters in Washington, D.C., feared that if it admitted fire could be beneficial in Southern forests and granted permission to burn, this would embolden burning advocates in the West. Thus, the agency continued to suppress and censor findings that supported use of fire, as was later revealed in Ashley Schiff’s 1962 book, Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service. At the same time, the Forest Service covertly allowed controlled burning in many instances in the South, sometimes under the guise of “administrative studies.”[16]

Finally in December 1943, the wartime manpower shortage for fighting fires and the swelling tide of evidence and agitation for permission to burn from within and outside of forestry caused Chief Forester Lyle Watts to sanction use of fire, but only in the South.[17]

FIRE IN THE WEST

Meanwhile, the January 1943 issue of the Journal of Forestry contained a startling and revolutionary article by a government forester, making a case for controlled burning in ponderosa pine forests of the West, based on both practical and ecological considerations. The disturbing light-burning movement that had been snuffed out by 1930 was suddenly reignited, and for the first time promoted in a professional journal by an experienced forester. Its appearance in the Journal of Forestry is remarkable in part because the journal’s publisher, the Society of American Foresters, had since its establishment in 1900 by Gifford Pinchot been closely if informally associated with the Forest Service. Nevertheless, the 1943 article was even more provocative than the Southern research papers that the Forest Service had suppressed.

The title “Fire as an Ecological and Silvicultural Factor in the Ponderosa Pine Region” promised that for the first time the case for using fire would be based upon its historical ecological role as well as its potential contribution to timber management. How is it that a government forester could publish such an insubordinate treatise at a time when the Forest Service worked hard to suppress anything that appeared to support controlled burning? The author, Harold Weaver, was employed by the Indian Service (today’s Bureau of Indian Affairs) in the Department of the Interior, a relatively little-known agency managing Indian reservation lands, and he built his case based on years of careful observations. Still, as David Clare recounts in Burning Questions: America’s Fight with Nature’s Fire, Weaver’s article barely passed through a gauntlet of skeptical reviewers. Also, Weaver’s byline in the journal carried the unusual disclaimer, “This article represents the author’s views only and is not to be regarded in any way as an expression of the attitude of the Indian Service on the subject discussed,” no doubt in an attempt to shield his employer from Forest Service wrath.[18]

When Weaver graduated with a degree in forestry from Oregon State College in 1928, he was “thoroughly imbued, at that time, with the incompatibility of [ponderosa] pine forestry and fire.” Then as he worked in central Oregon’s ponderosa forest, he was shocked when experienced woodsmen and even a renowned forest biologist—an expert on bark beetles—told him that the policy of excluding fire was a serious mistake. Weaver countered with a standard argument that pines couldn’t regenerate if fires were allowed, but the entomologist showed him a stand of young pines many of which had basal scars from having survived past fires. This opened Weaver’s eyes. Then, while examining young and old pines in many areas, he found they had survived fires at intervals mostly between 5 and 25 years. These burns had reduced fuels and thinned young trees, killing more young firs than pines. Inspecting a broad range of forests that were originally dominated by big ponderosas, he found that most had now experienced a long period without fire and they contained dense thickets of small firs and pines often malformed and stagnating.[19]

Disputing conventional wisdom, Weaver’s article used observations of tree vigor and other ecological evidence to assert that the thickets of young trees were heavily overstocked and incapable of developing into large trees without thinning by fire or some other means. He pointed out that thinning with fire was more economical than with ax or saw, and had the advantage of removing surface fuel as well. Weaver concluded that “converting the virgin [ponderosa] forest to a managed one depends on either replacing fire as a natural silvicultural agent or using it as a silvicultural tool.”[20]

Weaver’s article was doubtless viewed as apostasy by many foresters, although one national forest supervisor congratulated him saying, “It takes a lot of courage, even in this free country of ours, to advance and support ideas that are contrary to the trend of popular, professional thought.” In the years after his ground-breaking article appeared, other foresters who favored using fire in ponderosa pine contacted Weaver. He conducted burning experiments in ponderosa pine forests of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona, wrote more articles, and led field workshops. Responding to a 1951 article by Weaver, the distinguished University of California forestry professor Emanuel Fritz congratulated him for continuing to study the use of fire in silviculture, adding that “In the early days of forestry we were altogether too dogmatic about fire and never inquired into the influence of fire on shaping the kind of virgin forests we inherited. Now we have to ‘eat crow.’”[21]

Weaver’s work helped encourage another even more controversial advocate for controlled burning, this time located in California, where light burning promoters had long bedeviled the Forest Service. Harold Biswell had earned a PhD in botany and forest ecology at the University of Nebraska, a leading institution in ecological education. He also spent several years as a Forest Service researcher in the South, where he became acquainted with controlled burning in pinelands as it was being introduced in the 1940s. In 1947, Biswell became a professor of forestry and plant ecology at the University of California, Berkeley. As he departed the Forest Service, Edward Kotok, chief of research, admonished him to stay out of controlled burning when he got to California. He arrived just as “controlled” fire was being returned to the land.[22]

In 1945, the California legislature authorized state foresters to issue burning permits for chaparral and other brushlands to improve range and wildlife habitat. Upon arrival in Berkeley, Biswell soon began studying the effects of brushland burning. In the early 1950s he developed a method of firing the bottom of south-facing brushlands in spring under conditions where the fire would die out at a ridge-top when it reached wetter north-facing slopes. Livestock grazers and the state Fish and Game agency liked the results, but forestry authorities became alarmed when Biswell began experimental burning in ponderosa pine forests on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada.[23]

Biswell and Harold Weaver first met in 1951, and then began a long relationship reviewing each others’ projects and manuscripts, and as David Clare put it, “commiserating with each others’ trials.” Biswell was introducing controlled burning to large numbers of students, researchers, ranchers, wildlife specialists, and others through his university position, and this outraged some state and federal fire suppression authorities. They demanded that university administrators restrain him; but then influential supporters rose to his defense. Biswell persevered, serving for 26 years at the university, and together with Weaver gaining a cadre of collaborators, adherents, and other allies. Both of these principals lived to see the Forest Service make a stunning reversal of policy in the late 1970s and embrace prescribed burning in ponderosa pine and in other vegetation types as well.[24]

![Prescribed burn in a giant sequoia grove, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (National Park Service photo)]()

Prescribed burn in a giant sequoia grove, Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (National Park Service photo)

SMOKEY AND “THE BIG BURN”

However, immediately following World War II, while Weaver and Biswell were gaining converts among people connected to land management a slick national advertising campaign run by the Ad Council was selling the opposite message to the public at large.[25] The Wartime Council had employed Walt Disney’s Bambi as the symbol for fire prevention on posters that showed fire devastating wildlife habitat and the landscape, reinforcing the depiction of fire in the Bambi movie, a box-office sensation, as a malevolent force created by evil men. In 1944 Bambi was replaced by Smokey Bear, whose trademark slogan “Only you can prevent forest fires” has convinced tens of millions of Americans that fire in the forest is entirely destructive and not natural. His revised message of “Only you can prevent wildfires” hasn’t altered that perception. Seventy years later public misperception of fire impedes forest managers from implementing controlled burns and dissuades forest homeowners from safeguarding their property.

While Weaver and Biswell’s efforts focused on managed and accessible forests, another area of concern was raised by critics of the fire exclusion policy: A need to return natural fire to wilderness and backcountry. Until the early 1920s, a few high-level administrators in the Forest Service favored allowing some fires to burn in remote areas based on economic and other practical considerations but were largely shouted down, particularly after the Service chose a hard and fast policy of completely suppressing all fires following the Big Burn. Then in 1934, an unexpected dissenting voice arose from a Montana-born forester who had joined Pinchot’s Bureau of Forestry in 1902 and as a supervisor had battled the 1910 fires. The Journal of Forestry published an essay by Elers Koch, a well-respected forester in the Forest Service’s Northern Region, in which he lamented the effects of a complete suppression policy that entailed building roads, trails, and phone lines to a network of fire lookouts in the rugged backcountry of north-central Idaho.[26] Koch argued that the area was too rough and erosive for timber management and that forces of nature including fire should have been left alone to preserve its special wilderness character. Although the agency’s Washington office rebutted Koch’s contentions, in a sense it also confirmed them by establishing the 1.9 million-acre Selway-Bitterroot Primitive Area in 1936. Thirty-seven years later the ponderosa pine–dominated canyons of the Selway drainage became the site of the first natural fires deliberately allowed to burn in the Northern Rockies.

FIRE AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS

In 1924, Forest Service forester Aldo Leopold advocated establishing the first national forest wilderness area, the Gila, in the ponderosa pine–covered mountains of southwestern New Mexico. Ponderosa pine forests soon became a focal point for concerns about perpetuating natural ecosystems in the West. Ecologists argued early on that these fire-dependent forests and their big, long-lived trees were jeopardized by the policy of complete fire suppression. This case was presented in conclusive detail in 1960 by Charles Cooper in his Ecological Monograph, “Changes in Vegetation, Structure, and Growth of Southwestern Pine Forests since White Settlement.” Cooper concluded that a half-century of fire exclusion was the most important factor in irreversibly disrupting and degrading what had originally been a vast expanse of open-grown, big-tree ponderosa forest.[27]

In the early 1960s, ecological concerns were finally becoming a national issue. A blue-ribbon committee selected by the secretary of the Interior delivered a groundbreaking report on wildlife management in the national parks that recommended restoring fire as a natural process. The report emphasized that wildlife habitat cannot be preserved in an unchanged condition, but instead is dynamic, and that habitat suitable for many species must be renewed by burning. This report helped crack open a door for use of fire in national parks and wildlife refuges during the late 1960s and in national forest wilderness areas during the 1970s.[28]

By the 1970s, most ecologists recognized that natural agents of change like fire, floods, and hurricanes were vitally important in maintaining natural ecosystems, and that fire was an agent that humans had disrupted.[29] Today the concept of returning some form of fire as a process to native forests on public lands has gained scientific credibility. However, public opposition and a host of economic, legal, and logistical constraints stand in the way of reintroducing fire in most ponderosa pine forests, although not so much in large wilderness and backcountry areas.

Beginning in the late 1970s a series of changes in national forest fire policy have attempted to allow reintroduction of fire for ecological and other beneficial purposes. However 70 years of institutional history and publicity promoting and practicing fire exclusion hampers this transition. Meanwhile knowledge of the ecological importance of fire, and evidence supporting management of fire and fuels for practical reasons, continues to accumulate.

Hindrances to implementing fire management include a widespread naïve, Romantic vision in society that the ideal forest is one of undisturbed, even static, nature. Moreover, early ecologists promoted Clement’s undisturbed “climax” community model as a paragon rather than simply as the theoretical endpoint of forest succession, a position widely accepted by mid-twentieth-century foresters fixated on maximizing timber volumes. In contrast, the historical reality was often a fire-maintained “sub-climax” forest that featured resilient, fire-dependent tree species. For instance, fire-maintained forests featured towering white pines in New England, open groves of huge oaks and hickory in the Midwest, longleaf pine in the South, and sequoia, redwood, giant coastal Douglas-fir and pines in the West.

During the 1960s and 1970s Congress passed a variety of legislation aimed at protecting the environment. However, the Wilderness Act, Clean Air Act, the Endangered Species Act, and others were designed without good awareness of how fire-dependent ecosystems function. Instead, the legislation was crafted from a viewpoint that these ecosystems should be preserved unchanged. Throughout the ages, fires promoted biological diversity in the majority of American forests. Without fires, many of our magnificent trees would be rare or nonexistent because they grow in habitats that also contain shade tolerant (“shade loving”) trees that would otherwise displace them. Also a large assortment of fruit-bearing trees and shrubs, flowering plants, nutritious grasses, and the animals that depend on them owed their existence to fires. Nevertheless, while environmental legislation implicitly endorses continued suppression of natural (lightning) fires, regulations also make it hard to substitute prescribed fires for the suppressed natural fires.

RISE OF THE WILDLAND-URBAN INTERFACE

Since about 1970, when the first Earth Day celebration was held, the rapid proliferation of homes and other developments in American forests has greatly complicated all aspects of fire management. This broad and still growing forest residential zone termed the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) poses a major challenge for firefighters. Millions of dwellings are situated in hazardous forest fuels, and the buildings themselves can be ignited by airborne embers. This vulnerability exists despite widespread educational campaigns and monetary incentives promoting non-flammable materials for roofs, siding, and decks, and fuel reduction treatments around forest homes. The existence of many high-hazard homes makes it hard for fire managers to use prescribed burning in nearby forests or to allow natural fires even in forests that are miles away.

When homes are threatened by forest fires, a great portion of the limited firefighting resources are diverted to protecting them rather than containing the fire itself. Although there is widespread support for refusing or limiting protection to dwellings surrounded by dangerous fuels and those that offer unsafe access for fire trucks, it is difficult politically and emotionally for firefighters to actually deny that protection. Hence, firefighter deaths, such as the 19 Hotshots who perished trying to protect Yarnell, Arizona, in 2013 are often related to the WUI.

Ironically, although thinning coupled with slash disposal, and often prescribed burning, has clearly demonstrated effectiveness in greatly moderating the intensity of wildfires that approach the WUI, anti-logging sentiments and administrative barriers often prevent these practices.[30] Government financing of thinning and fuel treatments is very limited, even though cost-benefit analyses support them. Similarly, significant opposition remains to allowing natural fires to burn in wilderness and backcountry areas, highlighted by adverse reaction to the “let burn” policy during the fires in Yellowstone National Park in 1988. Nevertheless, repeated studies and observations indicate that returning fire to these forested areas tends to limit the size of later fires and has favorable ecological consequences.[31]

Information on fire ecology and the important role fire plays in forest ecosystems needs to be effectively integrated into the training classes that firefighters take. Firefighters who do not recognize fire as an integral component of the forest ecosystem may view their mission as a heroic attempt to save the forest, which may lead them to take inappropriate risks.

![Catface from multiple pre-1900 fires in a ponderosa pine. A thick growth of inland Douglas-fir is now replacing the pine as a result of fire suppression (Photo by author)]()

Catface from multiple pre-1900 fires in a ponderosa pine. A thick growth of inland Douglas-fir is now replacing the pine as a result of fire suppression (Photo by author)

MASTER OR SERVANT?

More than a century ago California timberman George Hoxie argued that we had best adopt fire in the forest as our servant; otherwise it will surely become our master.[32] Hoxie’s advice about adopting fire seems even more relevant today. A century of suppressing fire and ignoring the evidence of its ecological benefits has given rise to more severe and larger wildfires. The damage done to the land and to public policy can be reduced only if all stakeholders are willing to learn from the past and adapt to present conditions.

The challenge is to implement a more ecologically based and practical forest fire policy. Doing so is rooted in education but it begins with how we live. We cannot remove people from the Wildland-Urban Interface, nor stop them from moving there. But we can motivate and encourage them to live more intelligently and safely. Those living there must shoulder personal responsibility and not rely on government largesse and resources for their protection. State and local officials can follow the example of Montana’s governor Brian Schweitzer by challenging WUI residents to take responsibility and warning them not to depend on the government to save their forest home.[33] State and county governments should adopt regulations requiring fuel reduction, fire-resistant building materials, and adequate access roads as part of rural zoning or subdivision or building permits. More rural fire districts should be encouraged to map and evaluate homes and other developments and rate them in advance for feasibility and risk associated with providing protection. In conjunction with this rating, fire districts can point out critical deficiencies associated with protection of each homesite. Insurance and mortgage loan providers should be encouraged to consider wildfire hazards when evaluating applications.

All firefighters—whether wildland or structural—who work in the WUI, as well as WUI residents, should be educated about the intrinsic role of fire in the forest. An appreciation of fire as an important natural process provides a useful perspective for these people who have to deal directly with the threat and consequences of unwanted fires. Given the impact of climate change, disease, and insects on forests and forest health, it is becoming an ever-more critical need to educate the broader, general public about the ecological importance of fire and the management of forest fuels. The Forest Service already has an effective messenger in Smokey Bear when it comes to talking about forest fire. Though he unfortunately conveyed some wrong information about the role of fire in forests, his popularity could be leveraged for getting across a revised message about the ecological role of fire and how we can better adapt to fire-dependent landscapes. But whether or not Smokey is used, the message needs to be disseminated to all.

Legislative action at the local and state levels must be complemented by action at the federal level. It begins with educating Congress, federal land-management agencies, and stakeholders (including environmental groups and timber and lumber industry representatives) about forest conditions and the need for action. These groups need to be persuaded to set aside long-standing animosities so that laws and regulations can be revised to allow players like the Forest Service to return fire to the landscape and to conduct more widespread and strategically located thinning and fuel reduction operations. We know which ecological systems historically relied upon fire to thrive. It’s time to put that knowledge to work.

[1] R. E. Keane, K. Ryan, T. Veblen, C. Allen, J. Logan, B. Hawkes, “Cascading Effects of Fire Exclusion in Rocky Mountain Ecosystems: A Literature Review,” U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Res. Sta., Gen. Tech. Report-91 (2002).

[2] T. C. Nelson, “Fire Management Policy in the National Forests: A New Era,” Journal of Forestry 77 (1979): 723–25.

[3] Friederich-Karl Holtmeier, “Geoecological Aspects of Timberlines in Northern and Central Europe,” Arctic & Alpine Research 5 (1973): A45–A54.

[4] Stephen J. Pyne, Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 100–12.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Shortly before coming Forest Service chief in 1920, William Greeley published an article in The Timberman clearly defining the agency’s position: “‘Paiute Forestry’ or the Fallacy of Light Burning,” March 1920, 38–39; reprinted in Forest History Today Spring 1999: 33–37. See David Carle, Burning Questions: America’s Fight with Nature’s Fire (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2002), 27–31, for more on the debate between Henry Graves and William Greeley versus timber owner Stewart Eduard White that played out in the pages of Sunset magazine in 1920.

[7] F. D. Robertson, “Ecosystem Management of the National Forests and Grasslands,” (June 4, 1992) Memo to Regional Foresters and Research Station Directors, USDA Forest Service, Washington, DC.

[8] Pyne, Fire in America, 103; Stephen J. Pyne, Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910 (New York: Viking Penguin, 2001), 235–36; G. L. Hoxie, “How Fire Helps Forestry,” Sunset 34 (1910): 145–51.

[9] Pyne, Year of the Fires, 235.

[10] Gifford Pinchot, “The Relation of Forests and Forest Fires,” National Geographic 10 (1899): 393–403.

[11] F. E. Clements, “The Life History of Lodgepole Burn Forests,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service—Bulletin 79 (1910).

[12] R. Daubenmire, Plant Communities: A Textbook of Plant Synecology (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), 229–40; Pyne, Fire in America, 491–92.

[13] Mississippi congressman John F. H. Claiborne, quoted in Lawrence S. Earley, Looking for Longleaf: The Fall and Rise of an American Forest (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 13.

[14] A. L. Schiff, Fire and Water: Scientific Heresy in the Forest Service (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1962), 21–26; Pyne, Fire in America, 112–16.

[15] Pyne, Fire in America, 115–16.

[16] Schiff, Fire and Water, 75.

[17] Pyne, Fire in America, 116.

[18] Harold Weaver, “Fire as an Ecological and Silvicultural Factor in the Ponderosa Pine Region of the Pacific Slope,” Journal of Forestry 41(1): 7–14; Carle, Burning Questions, 60–61.

[19] H. Weaver, “Fire and Its Relationship to Ponderosa Pine,” Proceedings—Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference 1968(7): 127–49.

[20] Weaver, “Fire as an Ecological and Silvicultural Factor,” 7.

[21] Carle, Burning Questions, 62.

[22] Ibid., 57–58.

[23] Ibid., 58–59.

[24] Nelson, “Fire Management Policy.”

[25] Pyne, Fire in America, 176–79; R. H. Lutts, “The Trouble with Bambi: Walt Disney’s Bambi and the American Vision of Nature,” Forest and Conservation History 36(1992): 160–71.

[26] Elers Koch, “The Passing of the Lolo Trail,” Journal of Forestry 33(2): 98–104.

[27] Charles F. Cooper, “Changes in Vegetation, Structure, and Growth of Southwestern Pine Forests since White Settlement,” Ecological Monographs 30(2) (1960): 129–30.

[28] Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1962); A. S. Leopold, S. Cain, C. Cottam, I. Gabrielson, and T. Kimball, “Wildlife Management in the National Parks,” Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 28(1963): 28–45.

[29] Pyne, Fire in America, 493; E. P. Odum, Ecology and Our Endangered Life-Support Systems (Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, 1989).

[30] M. C. Johnson, D. L. Peterson, C. L. Raymond, “Managing Forest Structure and Fire Hazard—A Tool for Planners,” Journal of Forestry 105(2): 77–83; see also: Andrew T. Hudak, et al., “Review of Fuel Treatment Effectiveness in Forests and Rangelands and a Case Study from the 2007 Megafires in Central Idaho USA.” U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Res. Sta., Gen. Tech. Report-252 (2011).

[31] S. F. Arno and C. E. Fiedler, Mimicking Nature’s Fire: Restoring Fire-Prone Forests in the West (Island Press, Washington, D.C., 2005), 188–200.

[32] Hoxie, “How Fire Helps Forestry,” 145.

[33] Charles Johnson, “Governor: Homeowners Must Prepare for Fire,” Missoulian June 23, 2009, accessed at http://missoulian.com/news/local/governor-homeowners-must-prepare-for-fire/article_919e5766-eed7-5a1f-ac44-08f5ce2c0bb9.html.

Roger Underwood has kindly shared with us some research he’s recently done on the history of colonial forestry. It comes from his recent book Foresters of the Raj–Stories from Indian and Australian Forests, an anthology of stories dealing with the evolution of forestry in India during the latter half of the 19th century, and the development of models and systems that were ultimately exported all over the English-speaking world, including Australia and the United States (Yorkgum Publishing, 2013).

Roger Underwood has kindly shared with us some research he’s recently done on the history of colonial forestry. It comes from his recent book Foresters of the Raj–Stories from Indian and Australian Forests, an anthology of stories dealing with the evolution of forestry in India during the latter half of the 19th century, and the development of models and systems that were ultimately exported all over the English-speaking world, including Australia and the United States (Yorkgum Publishing, 2013).

Before there was a

Before there was a

![The Mission District burning. [Photographer: Chadwick, H. D. (US Gov War Department. Office of the Chief Signal Officer.) - US Archiv ARCWEB ARC Identifier: 524395 NARA National Archives and Records Administration]](http://fhsarchives.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/sfearthquake_fire.jpg?w=500&h=377)

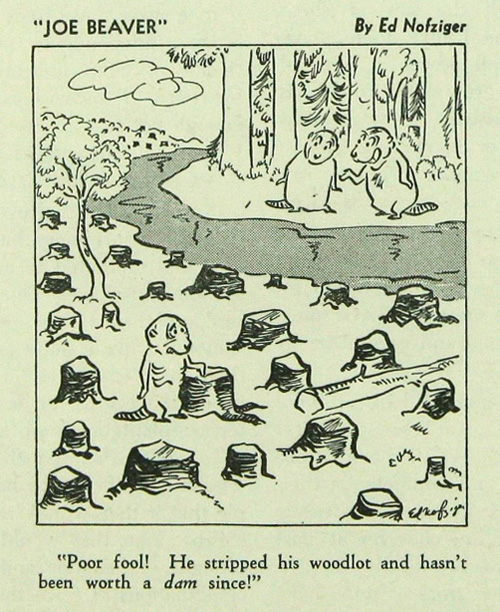

In July 1949 the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company debuted the first issue of its new company-wide magazine. Weyerhaeuser Magazine was targeted to company employees and featured company news across the various branches, as well as features on Weyerhaeuser employees both on the job and away from work. The inaugural issue of the magazine also introduced to the world a brilliantly-named character: Mr. Tim Burr.

In July 1949 the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company debuted the first issue of its new company-wide magazine. Weyerhaeuser Magazine was targeted to company employees and featured company news across the various branches, as well as features on Weyerhaeuser employees both on the job and away from work. The inaugural issue of the magazine also introduced to the world a brilliantly-named character: Mr. Tim Burr.

Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America is the latest film from Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey for PBS’s American Experience series. It is made in the traditional PBS style, perfect for the Olmsted neophyte and ideal for classroom use because of its length (55 minutes) and subject matter. You can stream it from the

Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America is the latest film from Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey for PBS’s American Experience series. It is made in the traditional PBS style, perfect for the Olmsted neophyte and ideal for classroom use because of its length (55 minutes) and subject matter. You can stream it from the

the focus of the Academy Award–nominated documentary film Wild By Law by Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey. All three men were leaders of the Wilderness Society, an organization formed in 1935 by Leopold, Marshall, and six other men to counter the rapid development of national parks for motorized recreation. The Wilderness Society supported projects like the Appalachian Trail but opposed others like the Blue Ridge Parkway because roadways like it were built at the expense of wilderness. (The tension between access to wilderness and protecting its integrity that led to the Society’s establishment is still a divisive issue today.) Zahniser, the executive secretary of the Society from 1945 until his death in 1964, carried forward the torch lit by Leopold and Marshall by writing the Wilderness Act and serving as its strongest advocate. The efforts of these and many other people have led to the protection of countless beautiful areas.

the focus of the Academy Award–nominated documentary film Wild By Law by Lawrence Hott and Diane Garey. All three men were leaders of the Wilderness Society, an organization formed in 1935 by Leopold, Marshall, and six other men to counter the rapid development of national parks for motorized recreation. The Wilderness Society supported projects like the Appalachian Trail but opposed others like the Blue Ridge Parkway because roadways like it were built at the expense of wilderness. (The tension between access to wilderness and protecting its integrity that led to the Society’s establishment is still a divisive issue today.) Zahniser, the executive secretary of the Society from 1945 until his death in 1964, carried forward the torch lit by Leopold and Marshall by writing the Wilderness Act and serving as its strongest advocate. The efforts of these and many other people have led to the protection of countless beautiful areas.