This is an expanded version of the review of Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens, by Steve Olson, which first appeared in the April-May 2017 issue of American Scientist.

When I visit environmental history–related locations, I typically bring back two reminders of the trip: photographs I’ve taken and rocks I’ve collected from the sites. When I returned from a trip to Wallace, Idaho, in 2009—a small, picturesque town located in the state’s panhandle and surrounded by national forests—I came home with rocks and a small vial of volcanic ash from Mount St. Helens.

![]()

The vial measures about 1.75″ in length but contains a great deal of information and memory.

The rocks came from outside the abandoned mine where, in 1910, Forest Service ranger Ed Pulaski and his men rode out one of the most famous wildfires in American history. Known as “the Big Burn,” the conflagration consumed 3 million acres in about 36 hours. Burning embers and ash fell upon Wallace, and fire consumed about half the town. The fire transformed the U.S. Forest Service, then only five years old; the lessons agency leadership drew from it—that more men, money, and material could prevent and possibly remove fire from the landscape—eventually became policy. The agency’s decision to fight and extinguish all wildfires, known as the “10 a.m. policy,” is one America is still dealing with because of the ecological impact removing fire from the landscape for half a century has had.

Seventy years later, another famous natural disaster coated the town in ash when Mount St. Helens, which sits in the middle of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southeastern Washington, erupted, sending some of its content miles into the air and drifting east towards Wallace and beyond. The vial I brought back contains some of that ash. The tiny container is a reminder that this disaster, too, transformed the Forest Service. It also transformed the U.S. Geological Survey.

![]() The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.

The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.

Just after the March 20th quake, some immediate protective measures were taken. The Weyerhaeuser Company, which was harvesting some of the last old-growth timber on its land surrounding Mount St. Helens on land it had owned since 1900, evacuated its 300 employees, and the Washington Department of Emergency Services advised everyone within 15 miles of the volcano to leave the area. But within a week, restlessness set in. After all, livelihoods were at stake. Area law enforcement couldn’t keep U.S. Forest Service roads closed to the public indefinitely and, given Weyerhaeuser’s economic and political influence in the region, public safety officials dared not close roads on its land. Beyond that, law enforcement simply didn’t have the resources to staff all the roads that snaked their way through the forest and around the volcano and nearby Spirit Lake.

On March 26, state and local officials, along with U.S. Forest Service personnel, the media, and a Weyerhaeuser representative, gathered in a conference room for a scientific briefing. The presenter, U.S. Geological Survey geologist Donal Mullineaux, along with his colleague Dwight Crandell, had spent two decades studying Mount St. Helens, publishing their findings in a 1978 report titled Potential Hazards from Future Eruptions of Mount St. Helens Volcano. Based on this work, the two were later considered founders of the field of volcanic hazard analysis. To the assembled group, Mullineaux reported that for the past thousand years, Mount St. Helens had erupted about once a century—most recently in 1857. Several eruptions had been violent lateral explosions, he noted, which had deposited white pumice as far as six miles away. He went on to describe possible characteristics of a future eruption: The area could be decimated without much warning by pyroclastic flows—powerful air currents of searing gas and pulverized rock capable of traveling at speeds in the hundreds of miles per hour. A landslide could hit the Swift Reservoir, about 10 miles to the south, and trigger a flood. Mudflows might sweep through the river valleys. And although lateral explosions were not well understood at the time, it was possible that another one could occur, blasting massive amounts of rock from the mountaintop directly into adjacent valleys. The next eruption was coming, the geologists had concluded in the report, “perhaps even before the end of this century.”

Dumbfounded by the direness of the warning and the imprecision of the timeline, a state official asked, “You mean to tell us that we as a nation can send a man to the Moon and you can’t predict if a volcano will erupt or not?” That was indeed the case. Mullineaux’s job was to convey the facts based on the geologic history. What to do with the information—whether to reopen roads to the public, for example, or to allow people to return to their homes and jobs—was up to the politicians and emergency planners.

Decisions about how and whether to restrict public access to the area quickly became political. In mid-April, the Forest Service designated two hazard zones. The red zone took in mostly Forest Service land to the north and east of the mountain. Its access was limited to scientists and law enforcement officials. However, an exception was made for lodge owner and newly minted folk hero and media darling Harry Randall Truman, who had lived beside the volcano for 54 years and strenuously defended his right to continue doing so. Refusing to leave, Truman remained in the red zone—no one had the political will to remove him. He even had the support and encouragement of the governor to stay. The blue zone extended to the southwest of the red zone; there, loggers and property owners could come and go during the daytime if they had permission. To the west and northwest of these zones sat prime Weyerhaeuser timberland. The Forest Service had no intention of restricting the lumber company’s property and alienating the powerful employer.

Washington Governor Dixie Lee Ray, a former biology professor who had improbably won the governor’s mansion in 1976 during the post-Watergate political backlash, had final say over the zones’ boundaries. Ray’s contrarian, acerbic personality—she delighted in insulting the press and encouraged Truman to stay despite the wishes of local officials—and her friendship with George Weyerhaeuser, president of the lumber company, made it unlikely that she would extend the blue zone’s boundaries into Weyerhaeuser land, as geologists and law enforcement wanted. The request to expand the blue zone sat on her desk unsigned the morning of May 18, when Mount St. Helens exploded and killed 57 people.

The real strength of Olson’s book lies in his handling of what happened after May 18. Before that, this reader was frustrated by his thirty-page digression into 100 years of history of the Weyerhaeuser family and company just to tell us that in 1980, after that initial earthquake alarmed his loggers and made them reluctant to go back to work, George Weyerhaeuser was not a man who’d change his mind after making a decision, and that decision was to keep logging. Olson follows this later with a chapter-length biography of Gifford Pinchot, the first Forest Service chief, that ends with a brief but essential discussion of the Forest Service’s multiple-use policies that came into play in the 1970s.

These digressions weaken and slow the book’s narrative. It feels like padding. He takes too long to get back to 1980, especially since his stated reason for writing the book was hearing of reports indicating that nearly all of the 57 victims of the eruption had flouted the law. The reports kindled in Olson a long-standing desire to understand why so many people had been so close to an active volcano.

The explanation that Governor Ray and others offered almost immediately afterward, a myth that still persists, was that nearly all were there illegally, having skirted around roadblocks and ignored warnings. Yet Olson found that of the 57 dead—who included campers and hikers, Weyerhaeuser loggers, sightseers, and people monitoring the volcano, such as geologist David Johnston—only Truman lacked permission to be there. In fact, most of the victims were outside the existing blue zone, even as the request to expand it sat on Ray’s desk. Had the disaster happened on a weekday, Olson notes, hundreds of Weyerhaeuser loggers could have been killed in the blue zone (which they had permission to enter during the daytime). None would have been there illegally.

The idea that the victims are to blame for their own deaths, Olson writes, “is the product of a carefully fabricated lie” invented and perpetuated by Ray and other public officials, who were “unwilling to take any blame for the disaster.” They claimed the victims had been warned and shouldn’t have been where they were. Ray stuck firmly to her story, and soon what might today be characterized as an “alternative fact” became, after much retelling, accepted as truth.

Olson’s anger about this prevarication is justified, and his book builds a solid case for condemning the politicians for their handling of the situation. However, those interested in digging further into the details of the actual cataclysm—scientific, personal, political, and otherwise—will find Richard Waitt’s 2014 title, In the Path of Destruction: Eyewitness Chronicles of Mount St. Helens, an invaluable and sobering read. Waitt, a volcanologist who analyzed ashfalls at Mount St. Helens in the weeks before its eruption, spent 30 years collecting accounts from hundreds of eyewitnesses, including survivors, scientists, rescue and recovery teams, and law enforcement. He rightly believed that these accounts could prove vital to researchers. He also combed through media archives to find the words of the victims themselves, and these make clear how little the public understood about possible hazards in May 1980.

Finally, Olson discusses the impact of the eruption on the scientific community. Those who had been working at the site were devastated. “Despite all their efforts at monitoring the volcano,” Olson notes, “they were unable to provide any warning of its eruption.” He concludes that

perhaps the greatest failure of the monitoring effort at Mount St. Helens was the insufficient attention devoted to the worst things that could happen. . . . A large event was possible but unlikely, and scientists still have difficulty dealing with low-probability high-consequence events. But without some knowledge of what could happen, the people around the volcano that Sunday morning were unprepared for what did happen.

The U.S. Geological Survey made significant procedural changes in the wake of the cataclysm. Having gained a better appreciation of the demands of conveying scientific knowledge outside scientific circles, the USGS established a new role in its ranks: Information scientists—experts knowledgeable about the data and experienced in media relations—would disseminate information to the press and the public. The agency also developed preparedness plans for hazardous volcanoes and created a standardized volcanic activity alert-notification system, which it modeled after the National Weather Service’s alert system for tornadoes and hurricanes. Its volcanologists also pressed on with renewed vigor. As a result, researchers’ understanding of volcanoes and lateral blasts has increased greatly because of Mount St. Helens—a consequence that should benefit many whenever the mountain rouses again.

Initially eager to get back to business as usual—which meant supporting the timber industry—the Forest Service ultimately saw the eruption as an opportunity for supporting scientific study. It seemed that before the ash had evened settled, debates over whether to conduct salvage timber operations and replant or instead turn the national forest lands around the volcano into living laboratory erupted with fury not unlike that shown by Mount St. Helens. With the unemployment rate in the surrounding area at 33 percent, local officials and business leaders favored logging, but scientists wanted to leave it alone to see what happened. Olson quotes a professor of zoology from Ohio State University as saying, “We have no site on the earth, apart from Mount St. Helens, where we can test some of these ideas of ours. We have needed beautifully clear, bare sterile land, and from this eloquent explosion, which no government on earth is wealthy enough to achieve for us, we have it virtually for free.”

![]()

Ominous clouds hang over the area of devastation from pyroclasitc flow in Coldwater Creek drainage/Green River area. Trees at left were untouched by the fast-moving blast on May 18. (USDA Forest Service – American Forestry Association Photo Collection)

The Forest Service initially estimated losses from the eruption at $134 million, which included an estimated one billion board feet of timber as well as infrastructure like bridges and buildings. Some 62,000 acres of its land suffered damage; 89,400 acres of state and private lands were affected as well. Though Olson correctly faults the Forest Service for being slow to accept the idea of setting aside enough acreage as a laboratory to truly be useful, he misses an opportunity to discuss what the agency ultimately did do in any detail—listen to its scientists and enable the study of how nature reacted to the event.

![]()

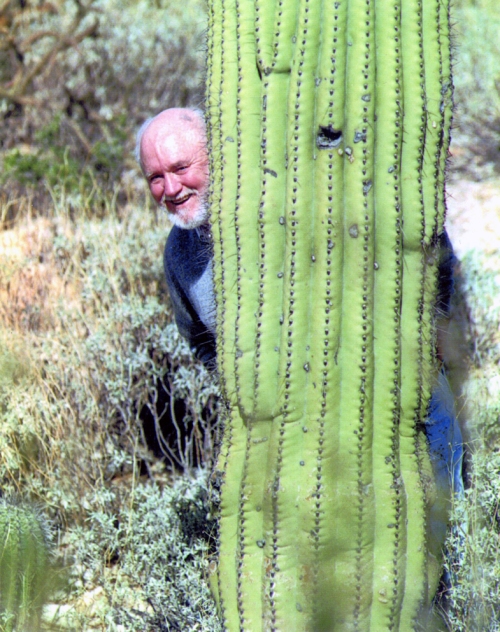

Jerry Franklin, Ecological Basis for Management of Northwest Coniferous Forests project leader, takes a close look at riparian vegetation returning along Coldwater Creek on St. Helens Ranger District in the Mount St. Helens Geological Area (USDA Forest Service – American Forestry Association Photo Collection)

His chapter “The Scientists” focuses on the impact experience by geologists and geology detailed above; the chapter after that, “The Conservationists,” in less than three pages skims over what “scientists” and “researchers”—no affiliation is given for these nameless figures—found under the pumice and what emerged from it. (The rest of the chapter actually has little to say about conservationists; instead it talks about what it’s like to visit the national monument.) The Forest Service’s decision to monitor instead of log allowed researchers including Jerry Franklin and James A. MacMahon the opportunity to study the massive disturbed area, much as the unnamed zoologist envisioned. They and others greatly increased their understanding of ecological processes in disturbed areas. This work led to a reexamination of traditional forestry practices, which ultimately contributed to the development of ecosystem forest management over the next decade. The land transformed by volcanic ash transformed the land management agency. That’s what I’m reminded of when I look at that vial of ash.

Filed under:

Historian's Desk,

This Day in History Tagged:

George Weyerhaeuser,

Gifford Pinchot National Forest,

logging,

Mount St. Helens,

U.S. Forest Service,

U.S. Geological Survey,

Weyerhaeuser Company ![]()

![]()

The early 1920s was a time of growing concerns over dwindling forest resources in the United States. In response to this perceived crisis, the American Reforestation Association was incorporated in Los Angeles in 1923. The stated aim for the group was “the saving of America’s greatest asset – trees. Not simply for sentiment but for the very life of the nation.” The official organizational motto was “The sapling of today is the man-timber of tomorrow,” and the group promoted tree planting, while also disseminating educational materials on the value of trees, hoping to influence the public on the need for laws to protect America’s forests.

The early 1920s was a time of growing concerns over dwindling forest resources in the United States. In response to this perceived crisis, the American Reforestation Association was incorporated in Los Angeles in 1923. The stated aim for the group was “the saving of America’s greatest asset – trees. Not simply for sentiment but for the very life of the nation.” The official organizational motto was “The sapling of today is the man-timber of tomorrow,” and the group promoted tree planting, while also disseminating educational materials on the value of trees, hoping to influence the public on the need for laws to protect America’s forests. The organization also worked closely with various Hollywood figures, hoping to use the growing film industry as a means of promoting the group’s cause of planting trees. From its base in Southern California, the Association recruited membership from across the country. The official membership emblem greeting potential new members was a woman in a crown of laurels (labeled “America”) with arms outstretched against a cross backdrop under the words “help save our trees.”

The organization also worked closely with various Hollywood figures, hoping to use the growing film industry as a means of promoting the group’s cause of planting trees. From its base in Southern California, the Association recruited membership from across the country. The official membership emblem greeting potential new members was a woman in a crown of laurels (labeled “America”) with arms outstretched against a cross backdrop under the words “help save our trees.”

Starting with Forks will introduce you to deepen the reader’s understanding of why his packhorse trips with Brown into “the High Lonesome” backcountry area—the Eagle Cap and Hells Canyon Wilderness Areas in eastern Oregon—that are the focus of much of Wilderness Journals brought him such joy and unleashed the naturalist-poet inside. Furthermore, in Forks Thomas helpfully explains and discusses the historical background or significance of a fork in the trail, such as a law or policy change, when necessary. The forewords and prefaces of Wilderness Journals and Hunting lack enough information or context for deeply understanding his heartfelt meditations on the beauty provided by federal natural resource management or the night sky in Alaska, or his distaste towards those who pay to hunt on game farms. The other two books supplement and complement Forks, and a few journal entries are split up between books depending on the topics. Each has entries several pages long, though they never feel like they are dragging on for several pages. Most all are a delight to read. Each book ends with an epilogue that offers his reflections on the journal entries and where he is now in his thought process.

Starting with Forks will introduce you to deepen the reader’s understanding of why his packhorse trips with Brown into “the High Lonesome” backcountry area—the Eagle Cap and Hells Canyon Wilderness Areas in eastern Oregon—that are the focus of much of Wilderness Journals brought him such joy and unleashed the naturalist-poet inside. Furthermore, in Forks Thomas helpfully explains and discusses the historical background or significance of a fork in the trail, such as a law or policy change, when necessary. The forewords and prefaces of Wilderness Journals and Hunting lack enough information or context for deeply understanding his heartfelt meditations on the beauty provided by federal natural resource management or the night sky in Alaska, or his distaste towards those who pay to hunt on game farms. The other two books supplement and complement Forks, and a few journal entries are split up between books depending on the topics. Each has entries several pages long, though they never feel like they are dragging on for several pages. Most all are a delight to read. Each book ends with an epilogue that offers his reflections on the journal entries and where he is now in his thought process. Wilderness Journals covers a narrow but pivotal time in Thomas’s life, from 1986 to 1999, when he found himself in thick of the northern spotted owl controversy and then reluctantly serving as Forest Service chief. The High Lonesome became a refuge from the pressures of work, a place to both recreate and “re-create” himself. On several occasions, he recorded the benefits of time spent in the wilderness. One in particular, written while he was chief, captures the feeling and offers a strong defense for maintaining protected wilderness areas, something Thomas strived to do while chief.

Wilderness Journals covers a narrow but pivotal time in Thomas’s life, from 1986 to 1999, when he found himself in thick of the northern spotted owl controversy and then reluctantly serving as Forest Service chief. The High Lonesome became a refuge from the pressures of work, a place to both recreate and “re-create” himself. On several occasions, he recorded the benefits of time spent in the wilderness. One in particular, written while he was chief, captures the feeling and offers a strong defense for maintaining protected wilderness areas, something Thomas strived to do while chief. Hunting Around World covers from 1986 to his last hunting trip in 2004 in Scotland; the entries on Scotland are the highlight of this book as he waxes poetic about the breathtaking Highlands countryside and falls in love with it. (Bob Model, who contributes the book’s foreword, hosted Thomas on his Scotland trips.) As someone who had studied the ecology of elk for much of his career, Thomas was excited about observing Scotland’s red deer, a member of the same species but a different subspecies. The contrast between hunting styles and rituals is quite interesting—one dresses in a “shooting suit” of tweed and wool when going “a-stalking” in Scotland, for example, and traditionally carries a walking stick to help traverse the uneven terrain. He also hunted in Argentina, Alaska, and other places, and some entries are from his trips into the High Lonesome. So one learns a good deal about the different cultures and attitudes about hunting as seen through Thomas’s eyes. His entries about hunting on game farms and hunting preserves versus a fair chase pursuit offer much to think about on that subject.

Hunting Around World covers from 1986 to his last hunting trip in 2004 in Scotland; the entries on Scotland are the highlight of this book as he waxes poetic about the breathtaking Highlands countryside and falls in love with it. (Bob Model, who contributes the book’s foreword, hosted Thomas on his Scotland trips.) As someone who had studied the ecology of elk for much of his career, Thomas was excited about observing Scotland’s red deer, a member of the same species but a different subspecies. The contrast between hunting styles and rituals is quite interesting—one dresses in a “shooting suit” of tweed and wool when going “a-stalking” in Scotland, for example, and traditionally carries a walking stick to help traverse the uneven terrain. He also hunted in Argentina, Alaska, and other places, and some entries are from his trips into the High Lonesome. So one learns a good deal about the different cultures and attitudes about hunting as seen through Thomas’s eyes. His entries about hunting on game farms and hunting preserves versus a fair chase pursuit offer much to think about on that subject.

If you find yourself in New York’s Adirondack Park, be sure to add a walk through Fernow Forest to the

If you find yourself in New York’s Adirondack Park, be sure to add a walk through Fernow Forest to the

With the arrival of talking pictures in 1929, Mary’s acting days were numbered. Born in 1892, by 1932 she could no longer play the young waif or ingenue; besides, fickle audiences had moved on to the “next big thing.” She recognized this change and effectively retired from film work the next year. But her philanthropic work continued unabated. During the first world war, she had barnstormed the country selling war bonds. In 1921, she helped launch the Motion Picture Relief Fund to help actors down on their luck. She was a supporter of the

With the arrival of talking pictures in 1929, Mary’s acting days were numbered. Born in 1892, by 1932 she could no longer play the young waif or ingenue; besides, fickle audiences had moved on to the “next big thing.” She recognized this change and effectively retired from film work the next year. But her philanthropic work continued unabated. During the first world war, she had barnstormed the country selling war bonds. In 1921, she helped launch the Motion Picture Relief Fund to help actors down on their luck. She was a supporter of the

The Hoo-Hoo in question was No. 2877, Mary Anne Smith. Mary Anne was born in Somerville, Tennessee, shortly before the Civil War. The Bulletin describes her early life as one of “hardship and suffering” as she grew up during the war and Reconstruction Period. “But,” the article notes, “no period, no matter how rife with struggle, hardship, and suffering, is without its romance, so in time young Mary Norman met and came to marry

The Hoo-Hoo in question was No. 2877, Mary Anne Smith. Mary Anne was born in Somerville, Tennessee, shortly before the Civil War. The Bulletin describes her early life as one of “hardship and suffering” as she grew up during the war and Reconstruction Period. “But,” the article notes, “no period, no matter how rife with struggle, hardship, and suffering, is without its romance, so in time young Mary Norman met and came to marry

The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.

The transformation began on March 20, 1980. After 123 years of dormancy, Mount St. Helens woke up. Seismometers had detected a 4.0 earthquake about a mile below the surface of the volcano, which is located in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in southwestern Washington. In the days immediately following, more quakes were recorded, as many as 40 an hour. These weren’t aftershocks—it was a volcanic swarm. Business owners, loggers, and the media demanded to know when the volcano was going to blow. As Seattle-based journalist Steve Olson discusses in his book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens (W.W. Norton, 2016), there was no easy answer: The science wasn’t there yet. But as Olson demonstrates, the lack of clear scientific guidance and an absence of straightforward jurisdictional relationships fostered government inaction at all levels, with disastrous results. Given recent seismic activity around Mount St. Helens (earthquake swarms were recorded in June and November of 2016, although these gave no indication of imminent danger), revisiting the events of 1980 seems especially timely.